From the gunslinging postwoman of Montana to the deputy marshal who patrolled the Plains, discover the seldom-taught stories of these icons of the American frontier.

Many stories about the Wild West depict it as a white place. Hollywood Westerns feature white lawmen, white outlaws, white cowboys, and white women. But the true Wild West was a place of rich diversity, and Black heroes made up an important part of its fabric.

In present-day Oklahoma, California, Texas, and other places, Black Americans lay down the law as deputies, delivered the mail as fearless postwomen, and roamed the Plains as cowboys. Many were born enslaved and searched the West, like their white countrymen, for freedom.

Below, discover the stories of Black Wild West heroes like Bass Reeves, the fearless deputy of Indian Territory, Buffalo Soldiers like Cathay Williams and Mark Matthews, and indomitable women like Mary Ellen Pleasant.

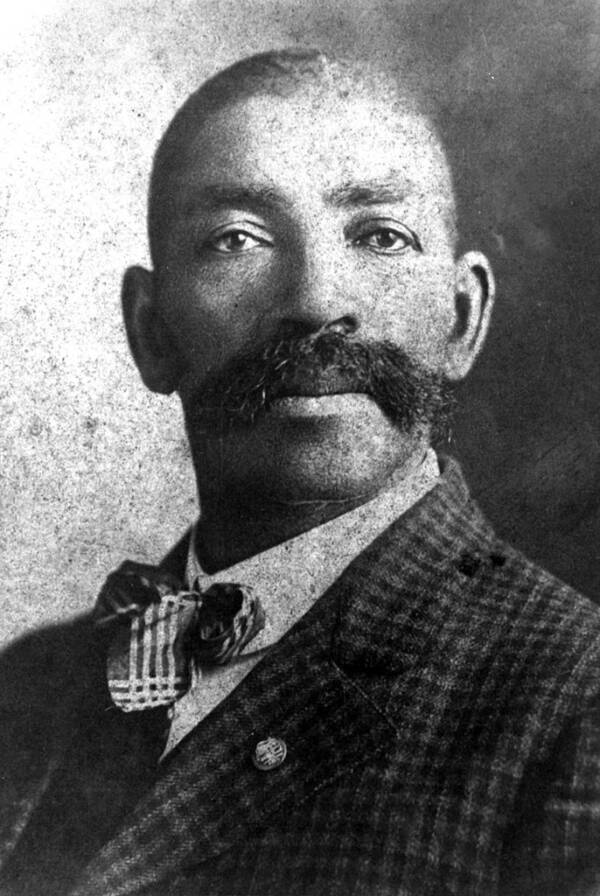

Bass Reeves: The Formidable Deputy Marshal Of Indian Territory

Public DomainSome believe that Bass Reeves helped inspire the fictional character of the Lone Ranger.

In the rowdy days of the Wild West, few places were quite as raucous as Indian Territory, a stretch of 75,000 square miles in present-day Oklahoma. But a Black deputy named Bass Reeves was determined to lay down the law.

Born a slave in 1838 in Arkansas, Reeves escaped bondage during the Civil War by beating up his master and fleeing to Indian Territory. There, he learned about the lay of the land, rubbed shoulders with the Indigenous Creek and Seminole people, and honed his skill with a rifle.

And when a judge named Isaac C. Parker showed up in the 1870s to bring the law to the lawless land, he looked to men like Reeves to get the job done. In 1875, Reeves became a Deputy U.S. Marshal — and quickly got to work.

Deputized, Reeves proved himself as an effective lawman. Creative — and as wily as the criminals he hunted — he began arresting scores of wanted men.

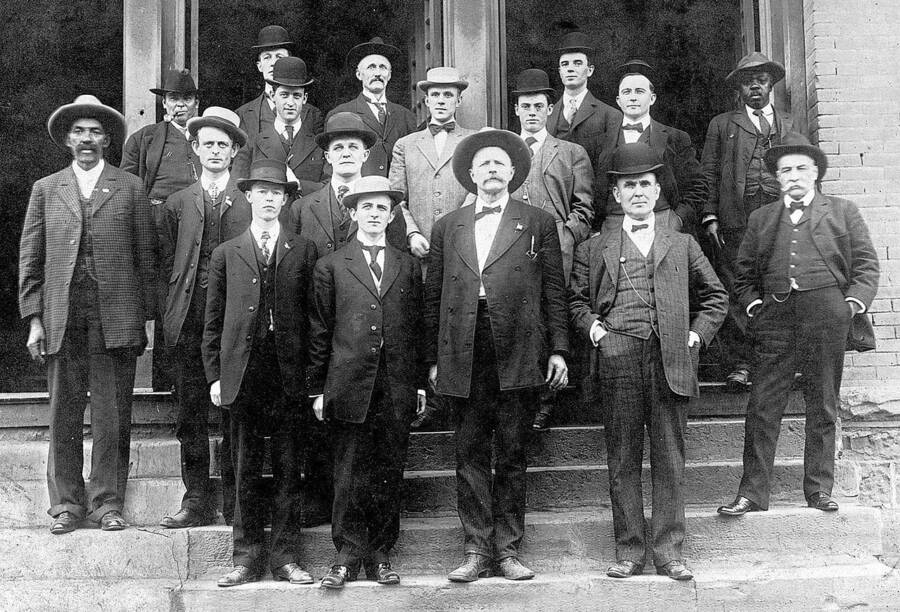

Public DomainBass Reeves, far left, standing with a group of fellow lawmen in 1907.

“Reeves would round up dozens of outlaws at a time — 12, 15, 16 — while most deputy marshals brought in four or five at a time,” Art Burton, the author of Black Gun, Silver Star, told the Washington Post.

Sometimes, Reeves disguised himself as a farmer or a preacher to fool criminals. Other times, he pretended to be a simpleton so that outlaws would let down their guard. And often, Reeves simply relied on his skill as a marksman. Once, he shot a fleeing outlaw from a quarter-mile away.

“Bass Reeves is the most successful marshal that rides in the Indian country,” raved the Daily Arkansas Gazette in 1891. “He… is a holy terror to the lawless characters in the west… It is probable that in the past few years he has taken more prisoners, from the Indian Territory, than any other officer.”

It’s no wonder why some believe that Reeves, who died in 1910 at age 71, inspired the adventurous tales of the fictional Lone Ranger.

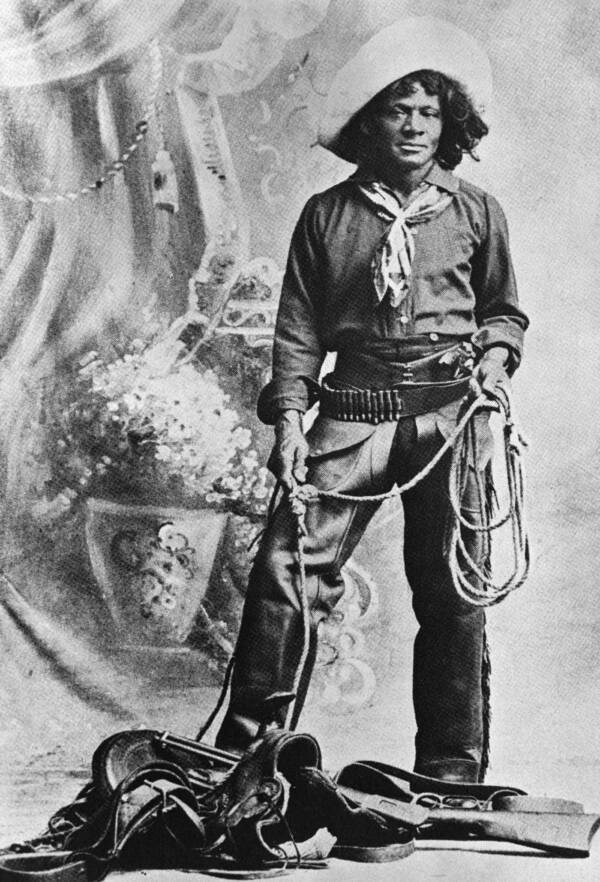

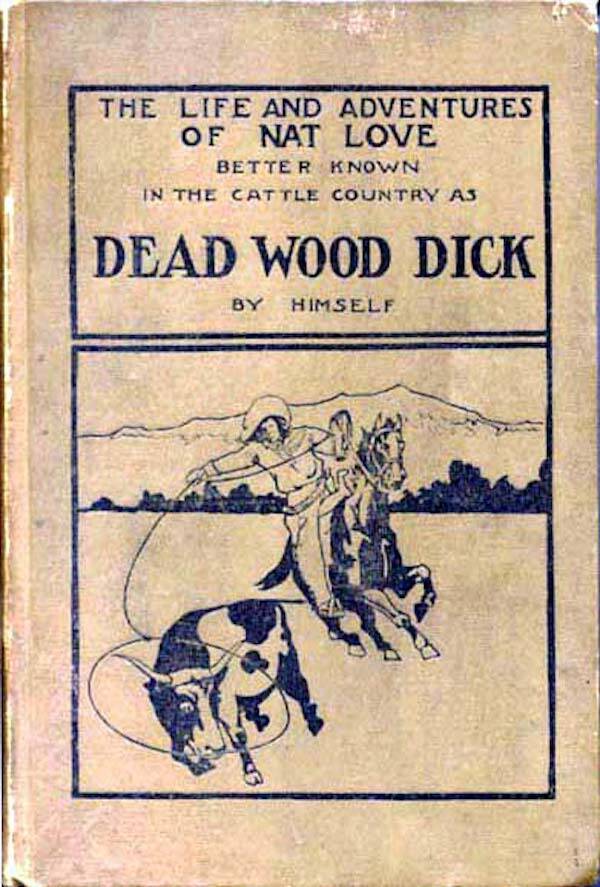

Nat Love: A Legendary Black Cowboy

Public DomainNat Love later detailed his exploits as a cowboy in his autobiography.

Part of the allure of the Wild West was that a person could be anyone they wanted to be. And Nat Love wanted to be a cowboy.

After spending the first part of his life enslaved, Nat Love left his home in Tennessee at the age of 15 in 1869. As Love later wrote in his autobiography, Life and Adventures of Nat Love, Better Known in the Cattle Country as ‘Deadwood Dick’, by Himself, he made a beeline for Kansas because “it was in the west, and it was the great west I wanted to see.”

In Dodge City, he marveled at the town’s “saloons, dance halls, and gambling houses.” And Love watched with great interest as Black and white cowboys swaggered through the city. Determined to be a cowboy himself, Love proved himself to the others by successfully riding an unbroken horse.

Accepted into their ranks, Love leaned into cowboy life. He drove cattle across Texas and Arizona, clashed with Native Americans, and allegedly rubbed shoulders with legendary outlaws like Jesse James and Billy the Kid.

Public DomainAs a cowboy, Nat Love often went by “Deadwood Dick” or “Red River Dick.”

Love also became a legend in his own right when he famously signed up for a contest in Deadwood, South Dakota, that challenged him to “rope, throw, tie, bridle, and saddle and mount” a horse as fast as possible.

“I roped, threw, tied, bridled, saddled, and mounted my mustang in exactly nine minutes from the crack of the gun,” he wrote. “This gave me the record and championship of the West… and my record has never been beaten.”

Though Love hung up his cowboy hat at the end of the century, he never lost his taste for adventure. He spent years working as a Pullman porter, which allowed him to travel the country. Then, Love worked as a guard for the General Securities Company until he died at age 67 in 1921.

His life, Nat Love later wrote, was “so full of action, which is but natural as the men of those days were men of action.”

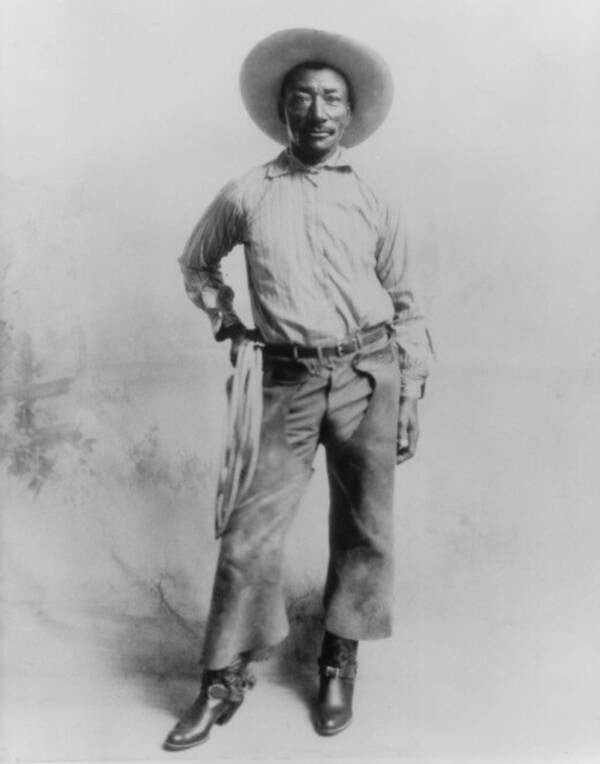

Bill Pickett: The Inventer Of “Bulldogging”

Public DomainBill Pickett traveled the world to show off his cattle-wrestling skills.

A descendant of formerly enslaved people, Cherokee tribe members, and white people, cowboy Bill Pickett invented the sport of bulldogging, or cattle wrestling, after observing how herder dogs subdued steers by biting their lips. What if, Pickett wondered, people could do the same?

In the 1880s, Pickett put his theory to the test. In front of astounded audiences, he wrestled steers by grabbing their horns and biting their lips, bringing the large animals down. By the turn of the century, Pickett was a rodeo star that one promoter dubbed the “Dusty Demon.”

Pickett showed off his sport in front of crowds all over the American West, as well as in England, Canada, Mexico, and South America. Sometimes, his work could be perilous. A crowd of 25,000 in Mexico City turned on Pickett after locals bet him that he couldn’t fight a bull. When Pickett subdued the animal, the audience threw bottles at him, breaking his ribs.

Library of CongressA statue of Bill Pickett cattle-wrestling in Fort Worth, Texas.

Pickett also encountered racist rodeos that didn’t allow Black performers. Then, he pretended to be a full-blooded Cherokee to get into the ring. But film studios were slightly more accepting, and cast Pickett in The Bull-Dogger (1921) and The Crimson Skull (1922) — the first all-Black Western.

When he died at the age of 61 in 1932 after an unbroken horse kicked him in the head, Pickett’s friend, the humorist Will Rogers, quipped: “Bill Pickett never had an enemy. Even the steers wouldn’t hurt old Bill.”

Pickett left behind a truly wild legacy. His somewhat controversial sport of cattle wrestling is still practiced today, and Pickett himself has been honored by the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum’s Rodeo Hall of Fame, the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame, and other institutions.

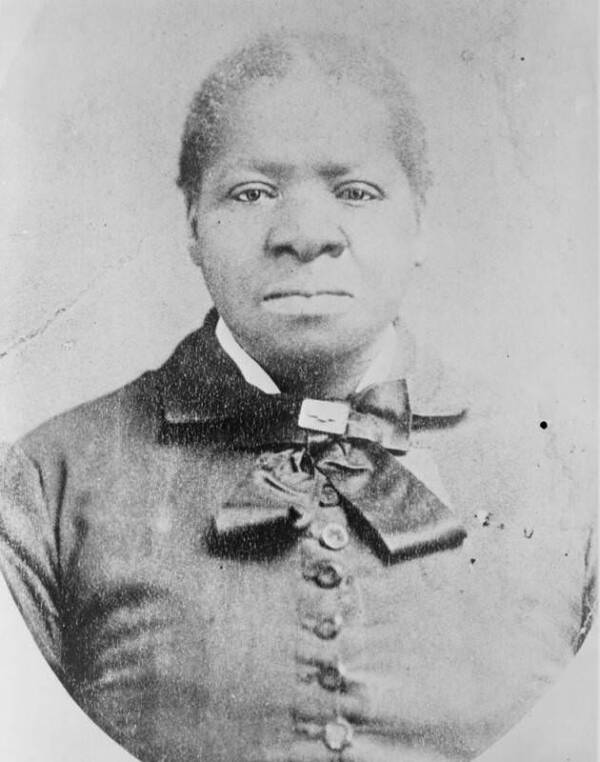

Biddy Mason: The Enslaved Woman Who Became A Real Estate Tycoon

Public DomainBiddy Mason fought for her freedom in the mid-19th century — and won.

Like many people in the Wild West, Bridget “Biddy” Mason was someone who forged her own path. But she overcame more than most in her journey from an enslaved woman to one of the richest people in Los Angeles.

Born enslaved in 1818, Mason spent most of her life following the whims of her master, Robert Marion Smith. A Mormon man, Smith forced Mason and other enslaved people to walk 1,700 miles from Mississippi to Utah, where Smith hoped to join a Mormon community. Mason trudged behind his caravan with her children, including a newborn baby.

But Smith made a mistake — he veered into California, a free state. There, slavery was illegal. And when Mason learned about this from free Black people living in California, she decided to do something about it.

Though Smith attempted to leave California for Texas, Biddy Mason had already made friends in California. A Black rancher named Robert Owens alerted the Los Angeles County Sheriff about Smith’s slaves, and the authorities stopped Smith before he could leave the state.

Library of CongressLos Angeles, circa 1886. During Biddy Mason’s life there, she became one of the city’s most prominent citizens.

Mason petitioned for her freedom on January 19, 1856. Though Smith attempted to bribe her lawyers, a judge granted her petition anyway — and Mason, and 13 members of her family, were finally free.

For the rest of her life, Biddy Mason worked to support other people. A nurse and midwife, Mason invested wisely and bought real estate in downtown Los Angeles. With her profits, she established a daycare, gave money to the poor, and helped found the city’s First African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Though Biddy Mason became one of the richest women in Los Angeles at the time, she was buried in an unmarked grave at the city’s Evergreen Cemetery after she died on January 15, 1891, at the age of 72.

It wasn’t until almost 100 years later, in 1988, that she was given a tombstone. Then, the mayor of Los Angeles and 3,000 members of the church she founded attended a ceremony celebrating her life.

Cathay Williams: The Buffalo Soldier Who Disguised Herself As A Man

U.S. ArmyA depiction of Cathay Williams, who disguised herself as a man in order to become a soldier.

The Wild West was a place of reinvention. But few reinvented themselves to the extent that Cathay Williams did. In 1866, she pretended to be a man in order to become a Buffalo Soldier on the American frontier.

Born enslaved in Missouri in 1844, Williams learned about the life of a soldier at a young age. After the Civil War broke out in 1861, Union soldiers came to occupy her hometown, and Williams, who was deemed “contraband,” was forced to work as a Union Army cook and a washerwoman.

Traveling with the Union Army, Williams saw the war up close.

“I saw the soldiers burn lots of cotton and was at Shreveport when the rebel gunboats were captured and burned on Red River,” she would later tell the St. Louis Daily Times in 1872. “Finally I was sent to Washington City and at the time Gen. (Philip) Sheridan made his raids in the Shenandoah Valley I was cook and washwoman for his staff.”

National Parks ServiceA group of Buffalo Soldiers patrolling Yosemite in 1899.

But when the war ended, Williams found few opportunities. So, she decided to disguise herself as a man and enlist in the U.S. Army.

According to Military.com, Williams was assigned to the 38th U.S. Infantry Regiment, one of six segregated Black infantry regiments. These Black soldiers were famously dubbed “Buffalo Soldiers” by the Native Americans who fought against them. This was supposedly because of their curly dark hair and fierce spirit, according to the National Parks Service.

And Cathay Williams — who presented herself as William Cathay — was one of them. She accompanied the 38th out west, where her regiment was tasked with protecting the construction of the intercontinental railroad.

Williams’ gender went unnoticed for about two years. But in 1868, doctors discovered the truth while they were treating her for a case of smallpox. Though she was honorably discharged, Williams’ legacy remains a remarkable one. She was the only woman to ever serve as a Buffalo Soldier and the very first Black woman to enlist in the U.S. Army.

Mary Ellen Pleasant: “The Mother Of Human Rights In California”

Public DomainMary Ellen Pleasant claimed that she helped fund John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

Like many others in the Wild West, Mary Ellen Pleasant spent most of her life trying to make it rich. But Pleasant went about attaining riches in a unique way and spent her money on causes she believed in, like abolition.

Some say that Mary Ellen Pleasant was born in Georgia, though Pleasant herself claimed to have been born in Philadelphia. Likewise, it’s not clear whether Pleasant, who was born in 1814, started her life free or enslaved.

But what does seem clear is that Pleasant learned a valuable lesson at a young age. According to The New York Times, her work as a domestic servant in Massachusetts taught her to observe others. Though she learned to read and write, Pleasant mostly used her observations as a de facto education.

“I have let books alone and studied men and women a good deal,” she later wrote in her autobiography.

After Pleasant’s first husband died in the 1840s, she made her way to San Francisco with her second husband, who she eventually separated from. And then, Pleasant used her skills of observation to make her riches.

Public DomainMary Ellen Pleasant used her powers of observation to build her fortune.

While working as a cook, Pleasant often eavesdropped on her wealthy customers and used what they said to invest the money she’d inherited from her husband. Before long, Pleasant owned a variety of properties and even listed herself as a “capitalist” on the 1890 census.

But Pleasant also donated her money toward worthy causes. When she heard about John Brown’s plan to raid Harpers Ferry, for example, Pleasant allegedly gave him $30,000. She even later requested that her gravestone be inscribed with the line: “A Friend of John Brown.” And after slavery was abolished, she focused on fighting against ongoing racial discrimination.

Her life was not without difficulty, however. Pleasant lost much of her fortune after her business partner, a white man named Thomas Bell, died. Though Pleasant and Bell may have made investments in his name because it was easier, Bell’s wife won control of the assets registered under him.

Mary Ellen Pleasant died in 1904, nearly penniless but still famous in San Francisco as the “Mother of Human Rights in California.”