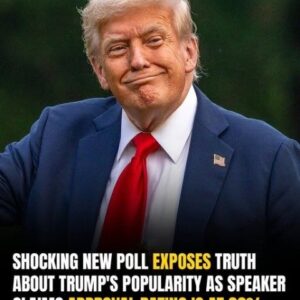

Budding ethnographer Michael Rockefeller vanished during his 1961 trip to New Guinea — then evidence emerged that he was killed and eaten by local tribespeople.

The great-grandson of John D. Rockefeller, aspiring explorer and ethnographer Michael Rockefeller had no interest in managing his family’s empire upon graduating from Harvard in 1960. Instead, he set out for the remote wilds of Dutch New Guinea to collect art made by the largely uncontacted Asmat people.

But before he could complete his second journey to meet the Asmat in November 1961, Rockefeller’s boat capsized off New Guinea’s southern coast and he was forced to attempt an arduous swim to shore. That was the last anyone ever heard from him.

Despite a gargantuan search effort and a media firestorm, Michael Rockefeller was never found and the authorities eventually declared him dead due to drowning in 1964.

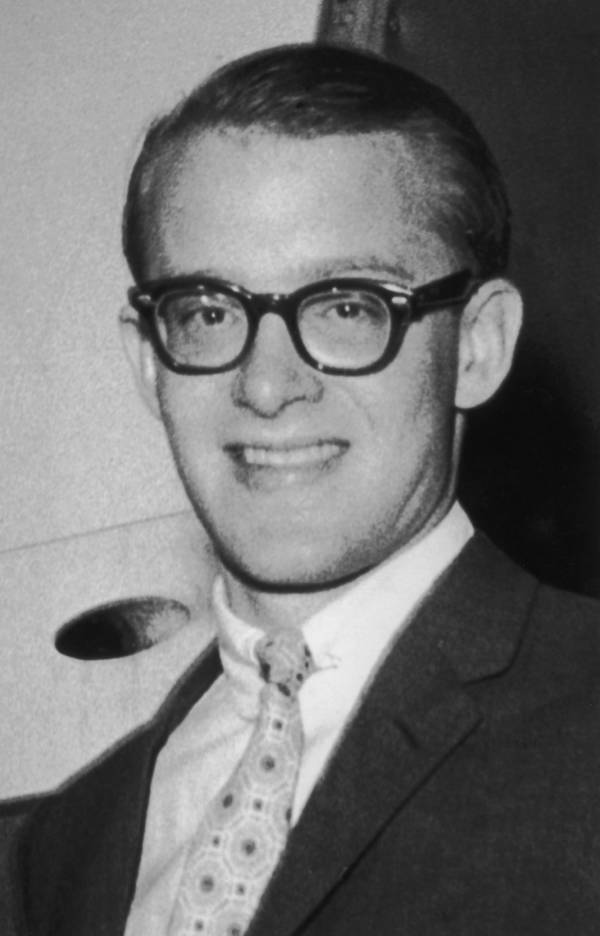

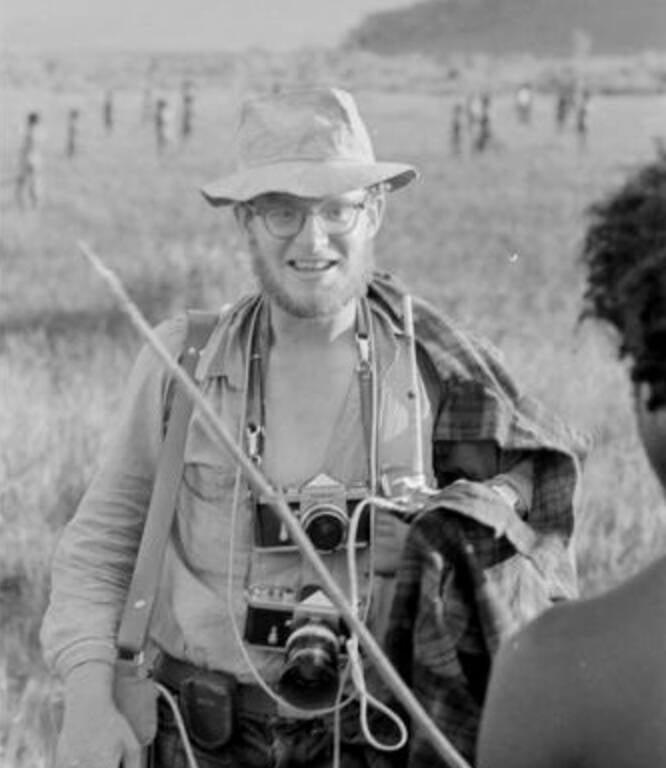

President and Fellows of Harvard University; Peabody Museum of Archeology and EthnologyMichael Rockefeller on his first trip to New Guinea in May 1960, just one year before his death.

But in the decades since, various independent investigators and writers claim to have uncovered evidence that the authorities actually buried the truth about Michael Rockefeller’s death because it was simply too horrific to reveal. Allegedly, Rockefeller made it to shore, but was murdered and eaten by the Asmat.

This is the haunting story of Michael Rockefeller.

Michael Rockefeller Embarks Upon A Life Of Adventure

Michael Clark Rockefeller was born in 1938. He was the youngest son of New York governor Nelson Rockefeller and the newest member of a dynasty of millionaires founded by his famous great-grandfather, John D. Rockefeller — one of the richest people who ever lived.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesNew York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller (seated) with his first wife, Mary Todhunter Clark, and children, Mary, Anne, Steven, Rodman and Michael.

Though his father expected him to follow in his footsteps and help manage the family’s vast business empire, Michael Rockefeller was a quieter, more artistic spirit. When he graduated from Harvard in 1960, he wanted to do something more exciting than sit around in boardrooms and conduct meetings.

His father, a prolific art collector, had recently opened the Museum of Primitive Art, and its exhibits, including Nigerian, Aztec, and Mayan works, entranced Michael.

He decided to seek out his own “primitive art” (a term no longer in use that referred to non-Western art, particularly that of Indigenous peoples) and took a position on the board of his father’s museum.

It was here that Michael Rockefeller felt he could make his mark. Karl Heider, a graduate student of anthropology at Harvard who worked with Michael, recalled, “Michael said he wanted to do something that hadn’t been done before and to bring a major collection to New York.”

He had traveled extensively already, living in Japan and Venezuela for months at a time, and he craved something new: he wanted to embark on an anthropological expedition to a place few would ever see.

Nielsen/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesMichael Rockefeller was determined to set out on his own and travel to the farthest reaches of the Earth.

After talking with representatives from the Dutch National Museum of Ethnology, Michael decided to make a scouting trip to what was then known as Dutch New Guinea, a massive island off the coast of Australia, to collect the art of the Asmat people who resided there.

Rockefeller’s First Expedition To New Guinea

By the 1960s, Dutch colonial authorities and missionaries had already been on the island for almost a decade, but many Asmat people had never seen a white man.

With severely limited contact with the outside world, the Asmat believed the land beyond their island to be inhabited by spirits, and when white people came from across the sea, they saw them as some kind of supernatural beings.

Michael Rockefeller and his team of researchers and documentarians were thus a curiosity to the village of Otsjanep, home to one of the major Asmat communities on the island, and not an entirely welcome one.

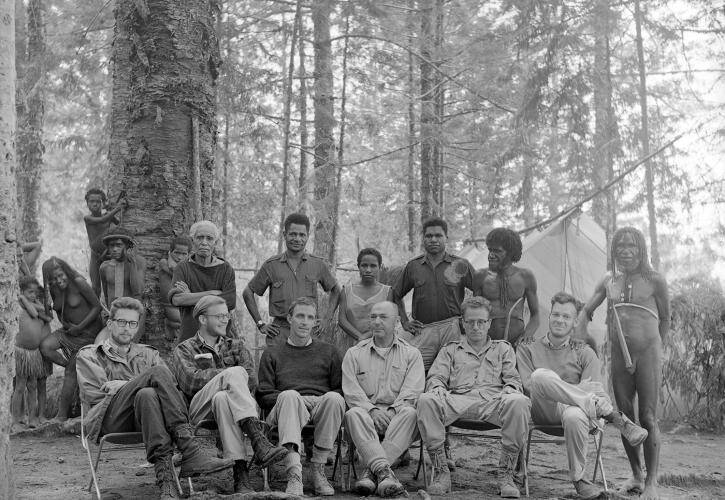

Eliot Elisofon/Harvard University Peabody Museum of Archaeology & EthnologyThe Harvard-Peabody expedition to New Guinea in 1961, with Michael Rockefeller seated second from right.

The locals put up with the team’s photography, but they didn’t allow the white researchers to purchase cultural artifacts, like bisj poles, intricately carved wooden pillars that serve as part of Asmat rituals and religious rites.

Michael was undeterred. In the Asmat people, he found what he felt was a fascinating violation of the norms of Western society — and he was more anxious than ever to bring their world back to his.

At the time, war between villages was common, and Michael Rockefeller learned that Asmat warriors often took the heads of their enemies and ate their flesh. In certain regions, Asmat men would engage in ritual homosexual sex, and in bonding rites, they would sometimes drink each other’s urine.

“Now this is wild and somehow more remote country than what I have ever seen before,” Michael wrote in his diary.

When the initial scouting mission concluded, Michael Rockefeller was energized. He wrote out his plans to create a detailed anthropological study of the Asmat and display a collection of their art in his father’s museum.

Michael Rockefeller Returns To Study The Asmat — And Disappears

Jan Broekhuijse/Harvard University Peabody Museum of Archaeology & EthnologyMichael Rockefeller during his 1961 expedition to New Guinea.

Michael Rockefeller set out once again for New Guinea in 1961, this time accompanied by René Wassing, a government anthropologist.

As their boat approached Otsjanep on November 19, 1961, a sudden squall churned the water and riled crosscurrents. The boat capsized, leaving Michael and Wassing clinging to the overturned hull.

Though they were 12 miles from the shore, Michael reportedly told the anthropologist, “I think I can make it” — and he jumped into the water.

Despite their efforts, they were unable to find Michael’s body. After nine days, the Dutch interior minister stated, “There is no longer any hope of finding Michael Rockefeller alive.”

Though the Rockefellers still thought there was a chance Michael might yet appear, they left the island. Two weeks later, the Dutch called off the search. Michael Rockefeller’s official cause of death was put down as drowning.

Eliot Elisofon/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesThe south coast of New Guinea, where Michael Rockefeller went missing.