Despite their immense contributions to the civil rights movement, these activists were largely ignored by the history books.

Who are the leaders of the civil rights movement? Certainly, names like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks come to mind. But it took more than one brave stand to make the movement succeed. It took millions.

These are the unsung heroes of the civil rights movement. They may not have given grand speeches or led marches, but their efforts informed, inspired, and enabled the movement in other ways.

Legal theorists like Pauli Murray helped dismantle discrimination through legislation, and Fannie Lou Hamer, who spoke without notes on live television for 13 minutes to draw attention to the poison of racism.

Many of the civil rights heroes on this list were unknown for reasons that spoke to the cultural and societal flaws of their time. In the male-led civil rights movement, leaders like Dorothy Height were pushed to the side. Others, like Bayard Rustin, were kept out of the spotlight because of their sexuality and political beliefs.

In the end, though, it took people from all backgrounds to move the civil rights movement forward. These heroes may have stood on the sidelines, but their efforts contributed to the movement’s success nonetheless.

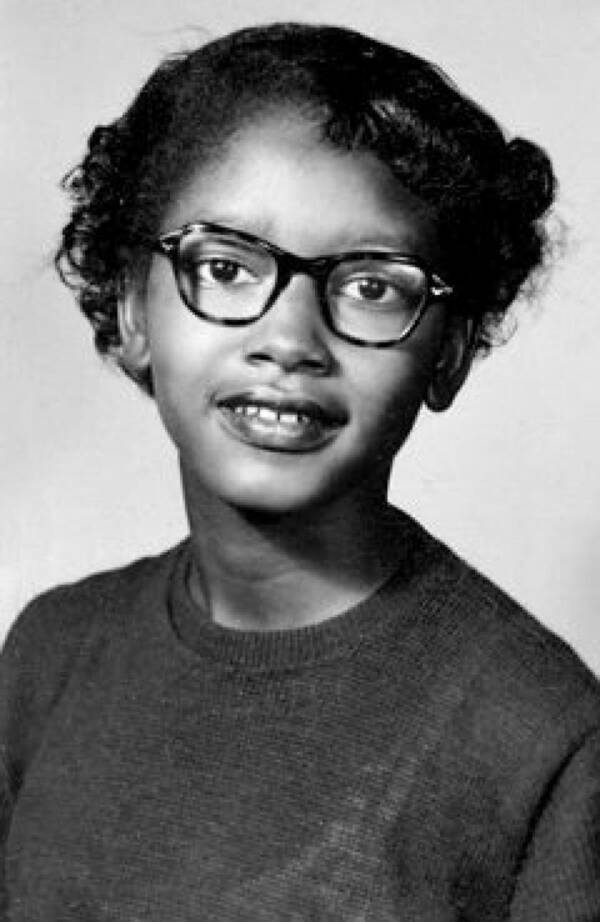

Claudette Colvin: The Brave Teenage Civil Rights Leader

Wikimedia CommonsClaudette Colvin was just 15 years old when she refused to change seats on a segregated bus.

In Montgomery in 1955, a Black girl refused to move to the back of the bus. Sick of segregation, she informed the driver that it was her constitutional right to sit anywhere she pleased. But her name was not Rosa Parks — it was Claudette Colvin.

“History had me glued to the seat,” she later recalled. “It felt as if Harriet Tubman’s hand was pushing me down on the one shoulder, and Sojourner Truth’s hand was pushing me down on the other.”

Just 15 years old at the time, Colvin had spent her young life quietly observing segregation in Alabama. She witnessed powerful injustices, like the execution of her neighbor for allegedly raping a white woman, and smaller ones, like when she tried to buy shoes.

“[Black people] couldn’t try on clothes,” Colvin explained. “You had to take a brown paper bag and draw a diagram of your foot … and take it to the store. Can you imagine all of that in my mind?”

Dudley M. Brooks/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesCivil rights leader Claudette Colvin still vividly remembers her arrest, especially the fear she felt when the police threw her in a jail cell.

By the time Colvin climbed onto a public bus on March 2, 1955, she and her class had started studying influential Black leaders in American history. With their stories racing through her mind, Colvin refused to obey the white driver when he told her to move.

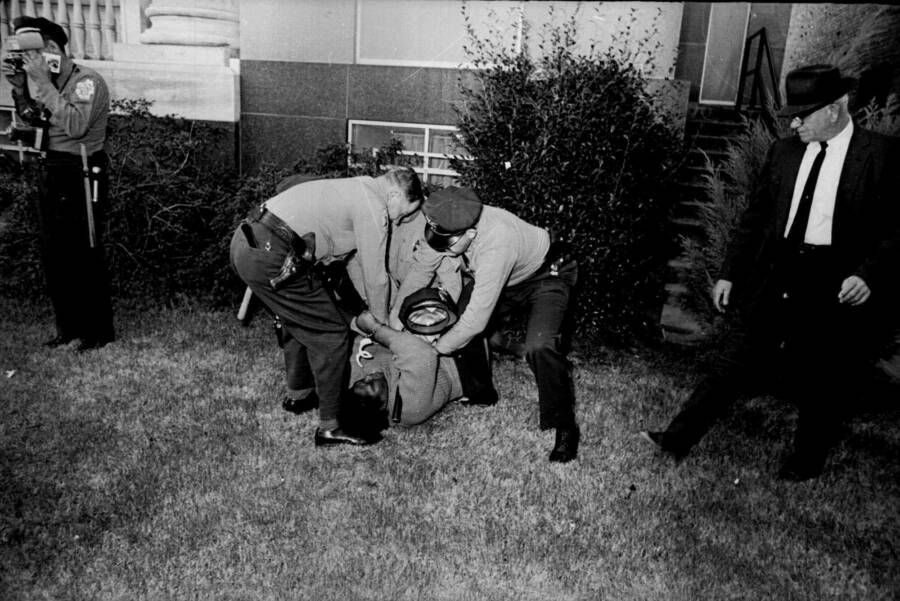

The driver called the police, who dragged Colvin off the bus.

“All I remember is that I was not going to walk off the bus voluntarily,” she continued. Her school books went flying everywhere, and Colvin repeatedly shouted “It’s my constitutional right!”

Despite her brave stand, Claudette Colvin didn’t spark protests like Rosa Parks did. She attributes this to her age, her dark skin tone, and the fact that she got pregnant a few months later.

“They didn’t think teenagers would be reliable,” Colvin recalled.

But Colvin got to have her say a few months later when she testified in Browder v. Gayle, the Supreme Court case that determined bus segregation was unconstitutional. On the stand, a lawyer asked her why she’d refused to move seats.

“Because,” Colvin, then 16, responded, “We were treated wrong, dirty, and nasty.”

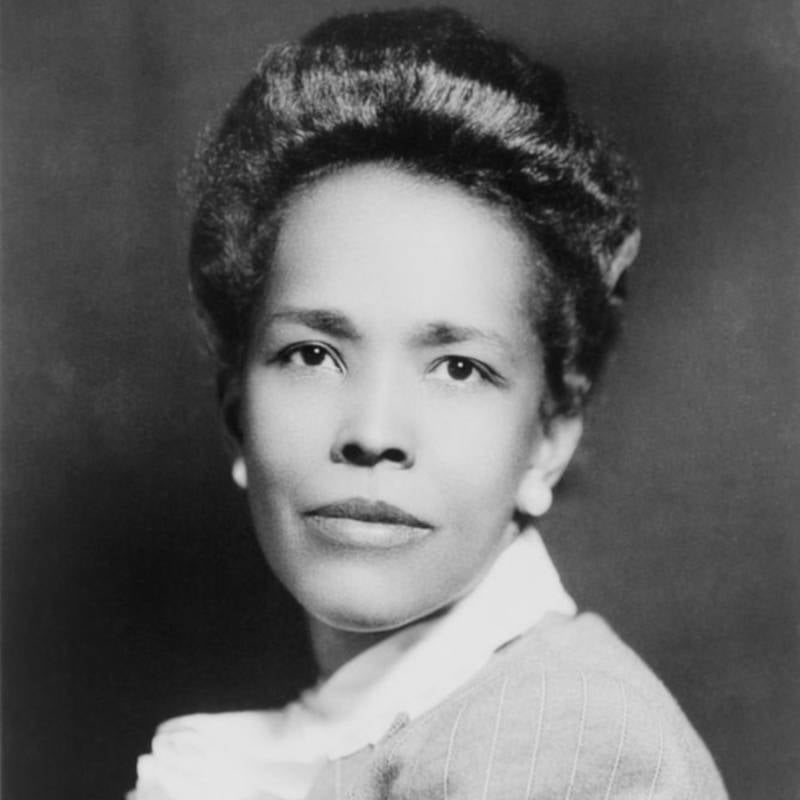

Ella Baker: The Great ‘Teacher’ Of The Civil Rights Movement

Library of CongressElla Baker influenced and inspired most civil rights organizations of her day.

Ella Baker helped shape not one but three major civil rights organizations: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

But she was never interested in publicity for her work. “I found a greater sense of importance by being a part of those who were growing,” Baker said. Indeed, other activists called her “Fundi” — Swahili for someone who teaches the next generation.

The granddaughter of enslaved people, Baker joined the NAACP in 1940. First a field secretary, then a director of branches, Baker traveled across the country and talked to Black Americans about their rights. During a workshop in Montgomery, Alabama, she even encouraged an NAACP member named Rosa Parks.

After Parks made her stand, Martin Luther King Jr. and other Black leaders formed SCLC. In 1958, Baker joined their ranks and soon played a crucial role in setting the agenda, planning events, and organizing protests.

Wikimedia CommonsCivil rights leader Ella Baker giving a passionate speech.

But SCLC prioritized the opinions of men, especially if they had a religious background, like King. Meanwhile, as SCLC increasingly focused on forcing change through lawsuits, Baker caught wind of a sit-in protest in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Inspired by the young activists, and convinced that great change could happen through actions like these, Baker called together Black students from across the country. With her support, they formed SNCC.

SNCC subsequently launched the Freedom Rides in 1961, which aimed to test national desegregation laws, and Freedom Summer in 1963, which aimed to register Black people to vote.

Though Baker influenced civil rights through her work with the NAACP, SCLC, and SNCC, she remains an unsung hero of the civil rights movement largely because she was a woman in a man-led movement.

SNCC leader James Forman even acknowledged that “many people helped to ignite or were touched by the creative fire of SNCC, without appreciating the generating force of Ella Baker.”

Annie Lee Cooper: The Civil Rights Hero Who Punched A Sheriff

TwitterAnnie Lee Cooper had tried voting multiple times in Selma without success before her fateful altercation in 1965.

Annie Lee Cooper didn’t set out to become a civil rights hero. On Jan. 25, 1965, all she wanted to do was vote. But while fighting toward that right, the face of a much-reviled Sheriff Jim Clark got in the way.

“I try to be nonviolent,” Cooper told Jet magazine a few weeks later, “but I just can’t say I wouldn’t do the same thing all over again if they treat me brutish like they did this time.”

Born in Alabama, Cooper had spent part of her life in the north, where she saw Black people voting. Cooper even registered to vote in Kentucky and Ohio. But in Selma, she was turned away from the voting booth again and again.

Once, the registrar told her she’d failed an impossible to pass literacy test. Other times, Cooper spent the entire day waiting to register, only to be sent home.

The Civil Rights Movement ArchiveAnnie Lee Cooper was charged with attempted murder.

So when Martin Luther King Jr. called for Black Americans to come to the Dallas County courthouse and vote en masse in the winter of 1965, Cooper took him up on the invitation.

She and other Black people had been standing in line for hours when Clark and his policemen arrived on the scene. As she watched the police break up the activists, Cooper muttered, “Nobody’s afraid of them.”

Clark told Cooper to go home and poked her in the neck with his billy club. To his shock, Cooper punched him in the face.

As the sheriff dropped to the ground, Alabama police piled on the 54-year-old Cooper. They dragged her to jail and charged her with assault and attempted murder.

“This is what happened today,” Martin Luther King Jr. said, soon afterward. “Mrs. Cooper wouldn’t have turned around and hit Sheriff Clark just to be hitting. And of course, as you know, we teach a philosophy of not retaliating and not hitting back, but the truth of the situation is that Mrs. Cooper, if she did anything, was provoked by Sheriff Clark.”

He continued, “At that moment, he was engaging in some very ugly business-as-usual action. This is what brought about that scene there.”

Annie Lee Cooper wasn’t an activist or a civil rights leader. But her punch embodied the frustration that many Black Americans felt.